The Holloway Corollary: When Being Good at Your Job Isn’t Enough

The Peter Principle says that ‘we rise to our level of incompetence.’ Basically, you’re good at your job so you get promoted, then rinse and repeat until you’re promoted into a job that you are not good at.

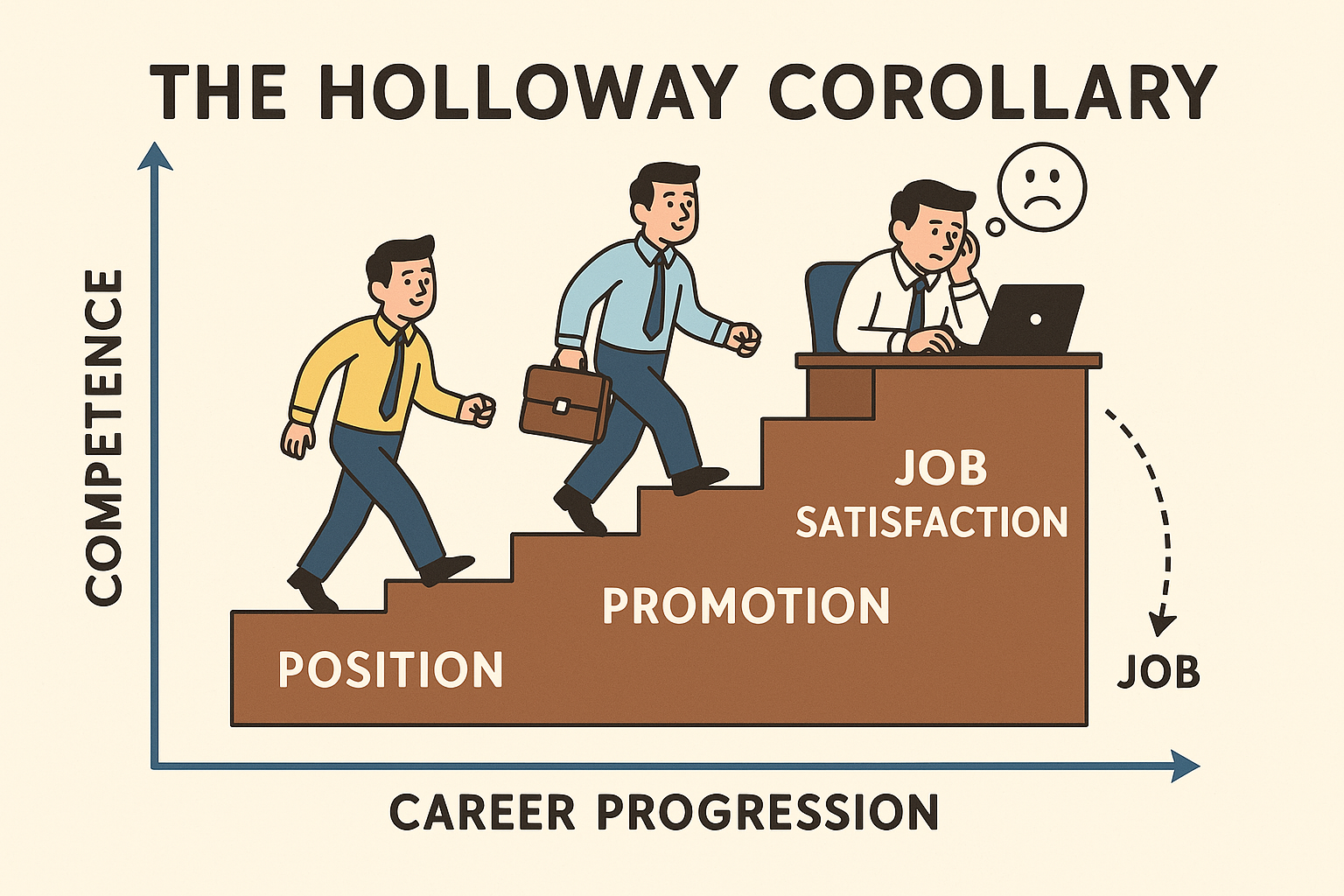

The Holloway Corollary

While the Peter Principle explains one career trap, I’ve observed another pattern just as common that I call the Holloway Corollary:

We rise to the point where our work no longer aligns with what energizes us – leaving us competent, but discontent.

The visual above illustrates this trajectory where competence continues to rise, even as job satisfaction drops off.

I’ve seen talented people become disengaged in roles they’re still capable of excelling in. A few examples:

- Someone who is great at managing teams but loves debugging the hardest problems

- A well-spoken, rockstar presenter who is taken away from working closely with customers

- An affable but introverted manager is asked to spend more time attending and leading meetings

- The maven that cannot work on new challenges

This often comes from being focused outside our strengths and passions. When the effort and reward no longer align, we burn out. Many people can continue competently, but not contentedly.

A Recent Example

A senior engineer I know was promoted to manager and spent months doing calendar Tetris, performance reviews, and paperwork (approvals, status updates). She and her teams were doing well, but she was miserable. Eventually, she stepped back into an IC role and rediscovered her spark. (She has not ruled out going back to management as part of the Engineer/Manager pendulum where senior people alternate between IC and manager, improving themselves and staying fresh along the way.)

Signs You’ve Hit the Corollary

Here are a few signs that you’re competent but discontent:

- You dread Monday mornings, even though you’re performing well

- You’re great at your job but secretly wish you were doing something else

- You find yourself nostalgic for earlier, less senior roles

You may find the Maslach Burnout Inventory helpful in assessing your current situation.

Possible Causes

Our motivations shift over time. What once excited us can slowly become exhausting. A job that once lit us up may eventually wear us down – even if nothing external changes. That change can happen suddenly but often happens gradually. For example, the adventurous 20-something who settles down in the 30s and focuses more on family or the employee-turned-founder who grinds with strong purpose. When your job no longer fits your current motivations, you naturally lose motivation.

Equally important are external factors such as company culture and economic conditions. Many people who purposely joined a small company will dislike the company after private equity takeover. Similarly, a serial job-hopper may stay put for a while when the market tanks and job openings are rare.

Career ladders often start with quick progress but eventually plateau, especially in companies with few senior roles or rigid title structures.

Structural or unconscious bias can limit advancement, leaving capable people stuck in misaligned roles.

Finally, I have seen some people unhappily grinding it, locked in due to golden handcuffs where their current compensation is appealing enough to justify staying longer.

Possible Solutions

How can you avoid falling victim to the Peter Principle and Holloway Corollary? Here are several ideas that you should apply routinely to keep up with change.

- Consistently ask for feedback

- Introspect to understand what you like and dislike – your ikigai or reason for working

- Craft your perfect job by identifying tasks you enjoy and seeking opportunities to incorporate them into your role

- Seek experiences that best fit your desires and actively negotiate away the experiences that drain you

- Avoid career moves (up, down, or sideways) that do not align with your interests

- Include your contentment into your career calculus – money is not everything

What’s one part of your current role that drains your energy — even if you’re good at it?

Conclusion

Many people may excel in one role and get promoted only to find themselves unable to do the job (Peter Principle) or disinterested in the job (Holloway Corollary). If the idea of competent yet discontent resonates with you, it might be time to take stock of what truly energizes you – before your competence becomes a quiet trap. The best careers aren’t just built on skill — they’re fueled by energy.

I hope you all can find meaningful work.